Why So Many Germans Emigrated in the 19th Century

Published by Gunar Bodendiek. Last updated on October 14, 2025.

Between 1820 and 1914, more than five million people left the German states to seek new lives overseas — the majority of them bound for North America. Today, their descendants make up one of the largest ancestry groups in the United States and Canada. But what drove so many to abandon the land of their birth? The story is one of hope and hardship, of faith, politics, and economic struggle — and it shaped millions of family histories still unfolding today.

1. A Fragmented Germany

Before unification in 1871, “Germany” was not a single country but a patchwork of kingdoms, duchies, free cities, and principalities — more than 30 in total. Each had its own rulers, laws, taxes, and even weights and measures. Life for ordinary people was highly local. A farmer or craftsman might never travel more than a few miles from home.

Yet this fragmented landscape also meant instability. Shifting borders, feudal duties, and regional restrictions made it difficult to own property or move freely. For many, emigration promised not only new land but personal freedom — the chance to start life without aristocratic oversight or rigid class barriers.

2. Economic Pressures and Rural Poverty

By the early 19th century, population growth in rural Germany far outpaced the availability of farmland. Inheritance customs divided property among heirs, creating ever-smaller plots that could no longer sustain families. At the same time, the Industrial Revolution disrupted traditional crafts and home-based trades.

Former weavers, blacksmiths, and day laborers found themselves out of work as factories and imported goods replaced small workshops. Rising grain prices, periodic crop failures, and natural disasters — such as the “Year Without a Summer” in 1816 — pushed many rural families to the brink of starvation. Letters from earlier emigrants describing cheap land and opportunity in America offered an irresistible contrast.

3. Political Upheaval and Lost Ideals

The failed Revolutions of 1848 sent a wave of politically motivated emigrants — known as the “Forty-Eighters” — out of Germany. These were intellectuals, students, journalists, and artisans who had fought for democracy, freedom of the press, and national unity. When reactionary governments restored control, many fled to escape imprisonment or persecution.

They carried with them not only ideals but skills. In cities like St. Louis, Milwaukee, and Cincinnati, Forty-Eighters founded newspapers, schools, and cultural societies that shaped German-American identity for generations. Their emigration turned political defeat into a new beginning across the Atlantic.

4. Religious and Social Restrictions

Religion also played a powerful role. Certain Protestant sects such as the Old Lutherans or Mennonites faced state interference or restrictions on worship. Catholic minorities in Protestant territories — and vice versa — could find advancement difficult. The promise of religious freedom in the United States attracted entire congregations who left together, founding German-speaking communities and churches in the Midwest and on the Great Plains.

Social class was another invisible barrier. In many areas, only firstborn sons could inherit land. Younger siblings had few prospects beyond military service or day labor. Emigration offered not just survival but independence — the chance to build something of one’s own.

5. The Role of Emigration Agents and Chain Migration

By the mid-1800s, emigration had become an industry. Agents traveled through villages distributing pamphlets promising fertile land in America or Australia. Steamship companies competed for customers, offering passage from ports like Hamburg and Bremen to New York, Baltimore, or New Orleans.

Once a few families from a village successfully settled abroad, they often encouraged others to follow. This “chain migration” created clusters of German-speaking settlements across the American Midwest, where newcomers could find familiar language, customs, and even local beer brewed to the old recipes.

6. Letters from the New World

Perhaps the strongest pull came from personal letters. Emigrants wrote home describing wide fields, high wages, and political freedom — often omitting the hardships of travel or frontier life. These letters circulated from family to family, inspiring neighbors and entire communities to follow the same path. For many who could barely afford the journey, such letters were both hope and proof that life could indeed be different.

7. A Journey of Hope and Uncertainty

Leaving Germany was not an easy decision. Families sold possessions, said farewell to relatives they would never see again, and endured weeks of cramped conditions on sailing ships. But for millions, the promise of land, liberty, and a future for their children outweighed the risks.

For descendants today, understanding the reasons behind that decision brings your ancestors’ courage into focus. Emigration was rarely an act of escape alone — it was an act of faith in a better tomorrow.

Want to Discover Why Your Ancestors Left?

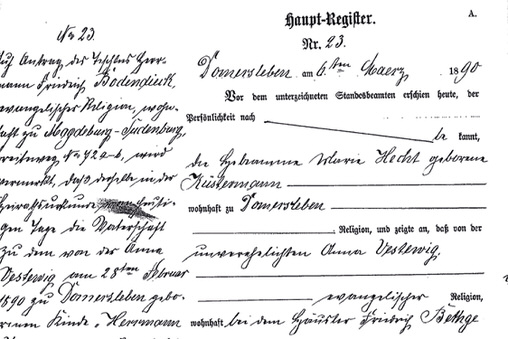

Every emigration story is unique. Economic hardship, family tradition, religious conviction, or pure adventure — the records often tell which applied to your ancestors. At My German Origin, I can help trace your family’s emigration path through passenger lists, church books, and regional archives to uncover the full story behind their departure.

Request a free feasibility check and start exploring the journey that changed your family forever.