Decoding Occupations in German Church Records

Published by Gunar Bodendiek. Last updated on October 14, 2025.

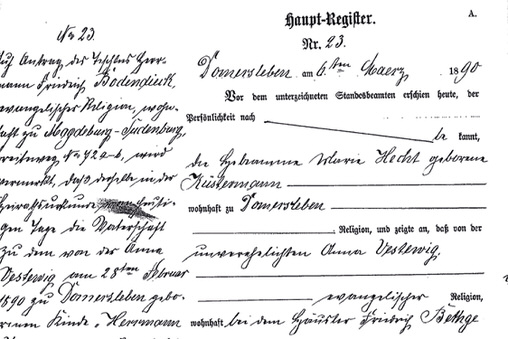

When tracing your German ancestors, you’ll often come across words in church records that look unfamiliar — terms like Böttcher, Schmidt, or Weber. These can be either surnames or occupations. In church records, context shows the difference: after the person’s name and set off by a comma it’s usually a trade (e.g., ‘Johann Müller, Weber’), while used as part of the name it’s a surname (e.g., ‘Johann Weber’). Information about the occupations can reveal a great deal about your ancestors’ daily lives and social standing. Understanding these job titles helps you see beyond names and dates to the real people who shaped your family’s history.

1. Why Occupations Matter in Genealogy

In German church records, occupations were often recorded next to a person’s name — especially for fathers, grooms, and witnesses. A single word can hint at social class, wealth, education, and even mobility. For example, the difference between an Ackerer (farmer owning land) and a Knecht (farmhand) tells you much about a family’s economic position.

Occupations also help confirm identities. If two men named “Johann Müller” appear in the same village, one listed as a Schmied (blacksmith) and the other as a Lehrer (teacher), you can distinguish them clearly across records.

2. Common Occupational Categories

Most jobs listed in 17th–19th-century German parish records fall into a few main groups. Below are examples of common terms and what they reveal about status or lifestyle.

Agriculture and Rural Life

Farming terms in German church records often reflect not only a person’s occupation but also their social and economic rank within the village. Before industrialization, these distinctions were crucial for understanding family wealth, inheritance patterns, and even marriage prospects. The terminology varied by region, but the following hierarchy is typical for many northern and central German areas from the 17th to 19th century:

- Vollmeier / Vollspänner / Großmeier / Großbauer: A full-fledged farmer who owned or leased a large, independent farm. These were the wealthiest peasants, often employing servants and farmhands. Their farms were typically subject to manorial or feudal obligations but provided significant income and status within the parish.

- Meier / Ackerer / Ackermann / Bauer: Literally “tiller of the field.” A general term for a farmer cultivating his own or leased land. The social standing was respectable middle-class within rural society — below the Vollmeier but above smallholders and laborers. In some regions “Ackerer” replaced “Meier” as a neutral term during the 18th–19th centuries.

- Halbmeier / Halbspänner: Tenant farmers who held roughly half the land of a Vollmeier. They usually owned part of their livestock and equipment but were less prosperous and often had to perform services or pay rent to the local estate or monastery.

- Köter / Köther / Kötner / Köthner: Smallholders who owned or rented a modest house (“Kate”) with a small garden or field, often just enough to support a family. Socially below the Meier class. Sub-categories appear in some regions:

- Großkötner / Mittelkötner / Kleinkötner: Large, medium, or small cottagers — distinctions based on the size of the holding.

- Kirchhöfer: A church tenant farmer, cultivating land owned by the parish or vicarage.

- Brinksitzer / Beibauer: Literally “those who sit on the edge.” Smallholders living on the outskirts (“Brink”) of a village, sometimes newly settled on cleared land. Their holdings were minimal and social rank modest.

- Heuerling / Heuerleute: Tenant laborers or sharecroppers who leased a small cottage and land in exchange for labor on the landlord’s farm. Economically among the poorest rural classes but extremely common in northwest Germany.

- Anbauer / Abbauer: Literally “one who builds up/down.” Settlers who had recently established (or divided) a farm from another property. The term describes the expansion or reduction of existing farms rather than a fixed social rank.

- Altsitzer: A retired farmer who had handed over his farm to an heir (often a son) but continued to live on the property, supported by the new owner. Also called Altenteiler in some regions; their support was usually guaranteed by a formal inheritance contract (Altenteil).

- Knecht / Ackerknecht: Male servant or farmhand; lower social class, often living in employer’s household.

- Magd / Dienstmagd: Female servant or farmhand; lower social class, often living in employer’s household.

- Hirte / Schäfer: Herdsman or shepherd; sometimes employed by several farms or the community.

- Winzer: Vintner or winegrower; common in southern and western Germany.

These titles can help you estimate your ancestor’s wealth and community role. A Vollmeier might appear in tax lists or serve as a village elder, while a Heuerling or Brinksitzer likely moved more frequently and left fewer written traces outside the church registers.

Crafts and Trades (Handwerk)

- Schmied: Blacksmith — an important, respected village trade.

- Weber: Weaver — one of the most common pre-industrial occupations.

- Schneider: Tailor — skilled artisan, often self-employed.

- Bäcker: Baker.

- Tischler / Schreiner: Carpenter or joiner.

- Zimmermann: House carpenter; frequently mentioned in construction-related records.

- Küfer / Böttcher: Cooper (barrel maker).

- Müller: Miller — often a position of moderate wealth and independence.

Service and Urban Occupations

- Hausknecht: Domestic servant or stablehand; low social rank but common in larger towns.

- Diener: Servant or attendant, sometimes in noble households.

- Wirt / Gastwirt: Innkeeper or tavern owner — respectable and socially connected role.

- Postknecht / Fuhrmann: Coachman, carrier, or transport worker.

- Schulmeister / Lehrer: Schoolteacher — educated, middle-class occupation often tied to the church.

Military and Administrative Roles

- Soldat / Musketier / Dragoner: Soldier, often listed when stationed in a parish temporarily.

- Beamter: Civil servant or government official.

- Förster / Jäger: Forester or gamekeeper, sometimes working on noble estates.

- Pfarrer / Pastor: Clergyman or parish priest.

Occupational Prefixes and Variations

Sometimes occupations include modifiers indicating status:

- Alt- or Jung- (old / young): distinguishes two people of the same name and trade, e.g. “Alt-Schmied Müller.”

- Meister: Master of a trade; ran his own workshop and took apprentices.

- Geselle: Journeyman; completed apprenticeship but not yet a master.

- Lehrling: Apprentice.

3. What Occupations Reveal About Social Status

Occupations in church records weren’t just job titles — they reflected a structured society. In rural areas, landowners and master craftsmen held respected positions, while servants, day laborers, and itinerant workers stood at the lower end of the social hierarchy. Clergy, teachers, and merchants formed a small but influential educated class.

Understanding these distinctions helps contextualize your ancestors’ lives: their economic circumstances, marriage prospects, and even mobility. A Schneider (tailor) might move from village to village, while an Ackerer could remain rooted in one parish for generations.

4. Challenges When Interpreting Old Job Titles

- Regional Variations: The same occupation could have different names depending on dialect — e.g., Schreiner vs. Tischler.

- Obsolete Professions: Some jobs disappeared with industrialization, such as Leineweber (linen weaver) or Feldhüter (field guard).

- Abbreviations and Handwriting: Terms are often abbreviated or written in Kurrent script; for example, “Ackr.” for Ackerer.

- Multiple Roles: Some people held several occupations (e.g., “Bäcker und Landwirt”), especially in small towns.

5. Bringing Your Ancestors’ Lives Into Focus

Once you understand what your ancestors did for a living, their world becomes clearer. A Weber family might have lived near a textile center, while a Müller likely worked near a stream or mill. Each occupation offers clues about where to look next — guild records, trade permits, or tax rolls can sometimes extend your research beyond the church book.

Need Help Reading Old Occupations?

Some job titles are rare or region-specific, and the handwriting in older records can make them hard to decipher. At My German Origin, I specialize in reading, transcribing, and translating old German documents. Whether it’s a church entry from 1750 or a faded marriage record, I can help you interpret every word and uncover the story behind your family’s occupation and status.

Request a free feasibility check to get expert help with your German records.